Finding out what controls the formation of sensory legs meant growing sea robins from eggs. The research team observed that the legs of sea robins develop from the three pectoral fin rays that are around the stomach area of the fish, then separate from the fin as they continue to develop. Among the most active genes in the developing legs is the transcription factor (a protein that binds to DNA and turns genes on and off) known as tbx3a. When genetically engineered sea robins had tbx3a edited out with CRISPR-Cas9, it resulted in fewer legs, deformed legs, or both.

“Disruption of tbx3a results in upregulation of pectoral fin markers prior to leg separation, indicating that leg rays become more similar to fins in the absence of tbx3a,” the researchers said in a second study, also published in Current Biology.

To see whether genes for sensory legs are a dominant feature, the research team also tried creating sea robin hybrids, crossing species with and without sensory legs. This resulted in offspring with legs that had sensory capabilities, indicating that it’s a genetically dominant trait.

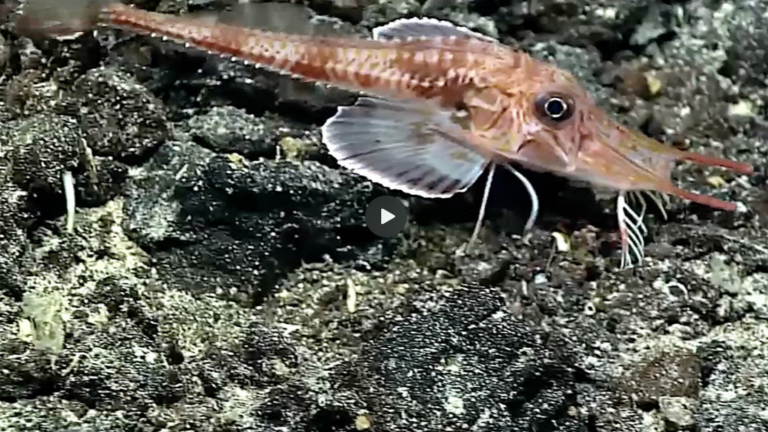

Exactly why sea robins evolved the way they did is still unknown, but the research team came up with a hypothesis. They think the legs of sea robin ancestors were originally intended for locomotion, but they gradually started gaining some sensory utility, allowing the animal to search the visible surface of the seafloor for food. Those fish that needed to search deeper for food developed sensory legs that allowed them to taste and dig for hidden prey.

“Future work will leverage the remarkable biodiversity of sea robins to understand the genetic basis of novel trait formation and diversification in vertebrates,” the team also said in the first study. “Our work represents a basis for understanding how novel traits evolve.”

Current Biology, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.08.014, 10.1016/j.cub.2024.08.042